Going Beyond Poverty Rates to Understand Financial Well-Being Through Data

When we talk about community health data, we often focus on where people aren't making ends meet — poverty rates, food insecurity, housing instability. These metrics matter, but they only tell part of the story.

In a recent episode of Data Chats, Metopio's data team explored a different angle: financial well-being — going beyond survival to talk about the capacity to weather a crisis, build stability, and move toward thriving. Here's what the data revealed, and why it matters for community health planning.

Credit Scores and the Foundation of Financial Stability

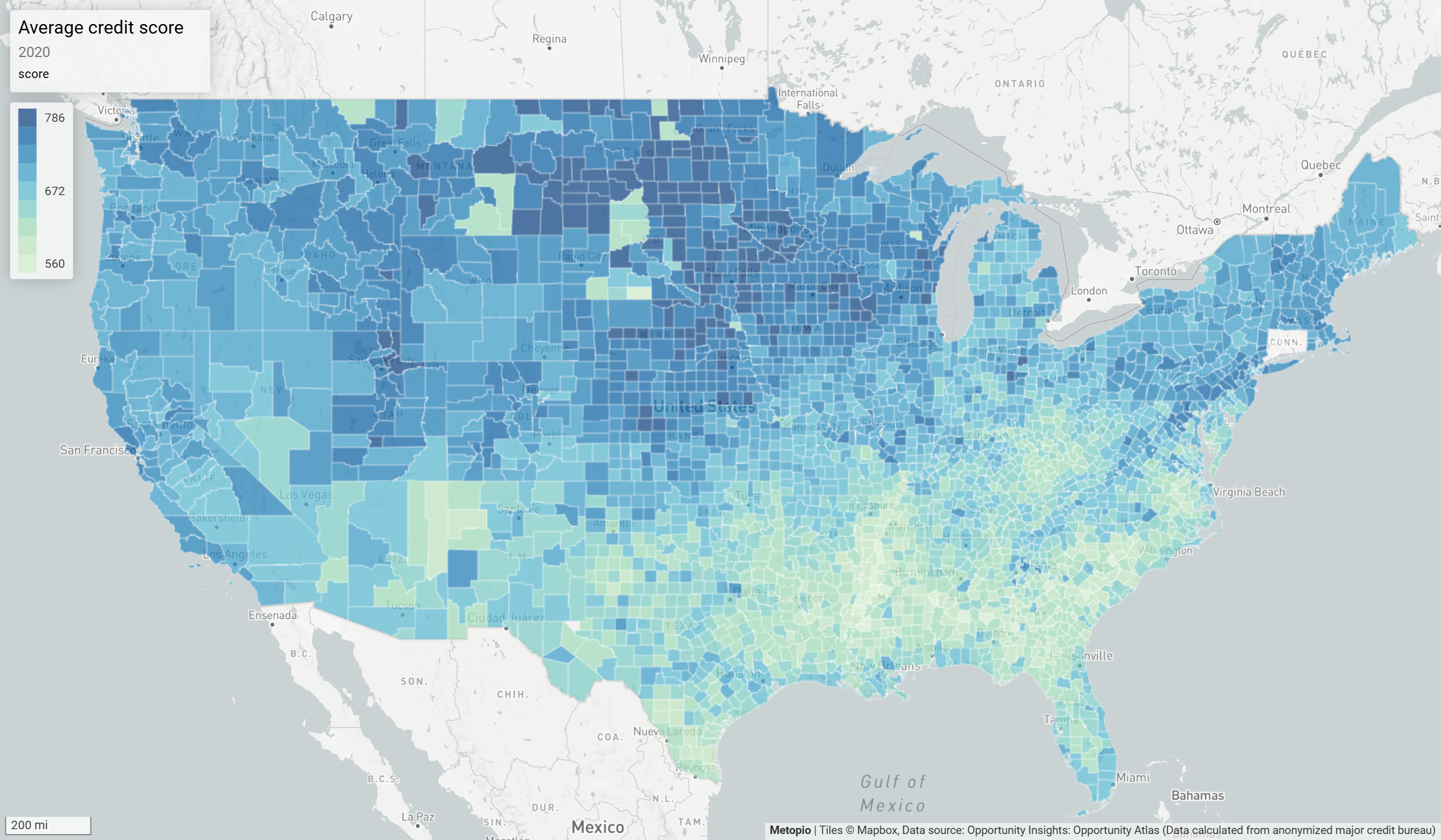

“Average credit score” is more than a number, it's a baseline of financial power — the ability to get a car loan, access credit, or qualify for better interest rates.

Data from the Opportunity Atlas shows pronounced regional differences. Southern states, particularly Louisiana and Mississippi, show significantly lower average credit scores among adults who grew up in the late 1970s.There's a visible line along the Mississippi River Delta, an area with a long history of poverty and segregation.

Our data scientists pointed out that these aren't just historical patterns; they reflect generational wealth gaps that persist today. When a financial crisis strikes — a medical bill, a broken-down car — people in these areas often have no one to call because their social support systems are under the same financial pressure.

The Debt Cycle: When Small Amounts Become Insurmountable

When our team is analyzing debt delinquency data, they’re looking at people who are 90 days or more late on debt payments. In many counties, the median debt in collections is under $1,000.

That means someone who couldn’t access $1,000 in the last 90 days is now facing collections, damaged credit, and higher interest rates on any future borrowing. It likely wasn’t overspending, but a crisis they couldn't absorb.

In many of these same counties, fewer than half of households have emergency savings of $2,000 or more. A relatively small financial shock — a car repair, a medical bill — can spiral into long-term debt.

The Inverse of Access: Credit Card Balances

At first glance, lower credit card balances in southern counties might seem positive. But the data tells a different story.

It doesn't necessarily mean people have paid off their cards, it more likely means folks couldn't get credit in the first place. They may be turning to payday loans or other high-cost alternatives, or they simply can't access the credit limits that people in other states or financial situations take for granted.

Meanwhile, in areas with higher credit card balances, people are using credit for “needs” (paying bills, covering emergencies, bridging gaps). Access to credit isn't always about overspending; it's about having flexibility when unexpected expenses arise.

Employment, Benefits, and the Ability to Build Wealth

Financial stability is highgly related to what kind of jobs are available and whether those jobs come with benefits.

Data on employer-based retirement plans shows stark geographic disparities. Minnesota stands out, not just because of household wealth, but because of employers like 3M and Mayo Clinic who offer good retirement benefits. Louisiana and Mississippi typically have far lower coverage.

This speaks to a bigger system issue. Beyond just “employment”, people need to consider employment with benefits, stability, and a path toward building something for the future.

Median Net Worth and Generational Wealth

Next, our team layered in median net worth to make the picture even clearer. In California cities with high property values, families can build wealth through home ownership. In southern states with lower credit scores, higher debt delinquency, and fewer employer benefits, that wealth-building opportunity simply doesn't exist at the same scale.

Although these issues are often attributed to individual choices, it's often about systemic access to credit, jobs with benefits, and the financial tools that allow people to weather a crisis and move toward stability.

What This Means for Community Health Planning

Financial well-being and health are inextricably linked. Medical debt, transportation barriers, food insecurity — all of these are shaped by whether someone has $1,000 in savings or access to a credit card when an emergency strikes.

When you're planning CHAs, CHIPs, or community benefit strategies, these financial well-being indicators add critical context. They show:

Which communities are most vulnerable to health-related financial shocks

Where people lack the resources to follow through on care recommendations (prescriptions, follow-up visits, preventive care)

How systemic barriers, not just individual behavior, shape health outcomes

The bottom line: Financial well-being data doesn't replace traditional health metrics; it deepens them. It helps you see not just where people are struggling, but why — and what it would actually take to move the needle.

If you want to explore specific financial well-being data for your community, Metopio's platform includes curated indicators on credit scores, debt, savings, employment benefits, and more — all ready to analyze at the county, city, or neighborhood level. Schedule a demo to see how these insights can inform your next CHA or CHIP.