Going Deeper on Food Insecurity Data

By Annie Elliott, Senior Data Analyst at Metopio, and Heather Blonsky, Vice President of Data at Metopio

Why Food Insecurity Needs a Closer Look

When public health teams and hospitals begin exploring food insecurity in their communities, there’s an obvious starting point: pull up a food insecurity indicator and see where the rates are highest. But as Annie Elliott, Senior Data Analyst, and Heather Blonsky, Vice President of Data at Metopio recently discussed, that surface-level view risks missing critical context.

"Food insecurity is a great indicator, but it's just one piece of the puzzle," Elliott explains. "When we start layering in other data — like SNAP benefit adequacy, transportation access, and where people can actually spend those benefits — we get a much richer understanding of what's really happening in a community."

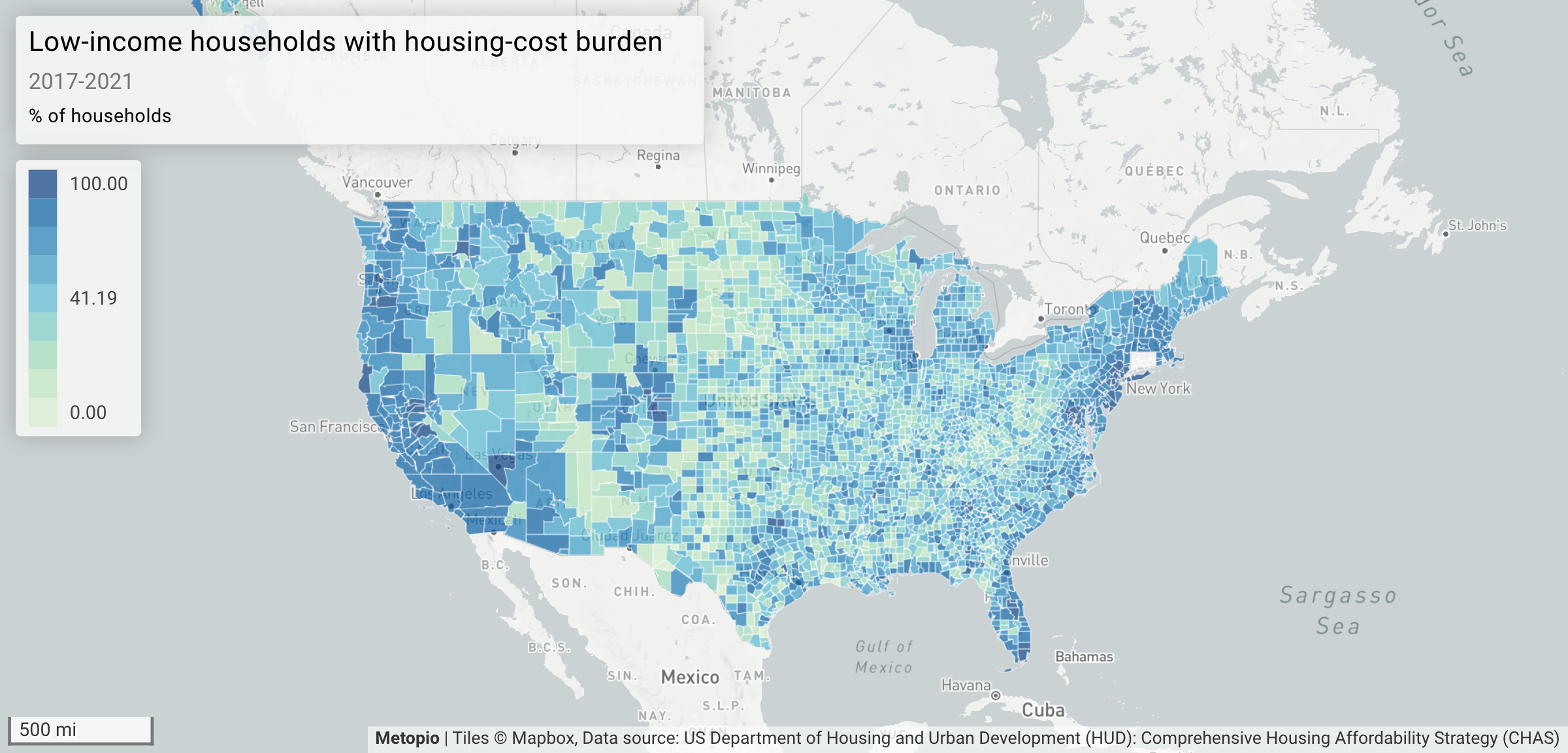

The cost of living varies dramatically across the United States, which means poverty and food insecurity don't look the same everywhere. A family in rural Texas faces very different challenges than one in a Colorado ski town, and the data needs to reflect those realities.

The SNAP Meal Gap: Where Benefits Fall Short

One of the most revealing indicators Metopio tracks is the SNAP Meal Gap — the difference between the value of SNAP benefits and the actual cost of a meal in a given county.

"Anything positive on this map means people's SNAP benefits don't cover the cost of a meal," says Elliott. "And what you see is exactly what you'd expect — the coasts are more expensive. But then you zoom into a state like Colorado, and the story gets more interesting."

In Colorado's mountain counties — Eagle, Summit, and Routt — where ski resorts drive up the local cost of living, the SNAP meal gap is strikingly high. Meanwhile, counties on the high plains show that SNAP benefits can adequately cover meal costs.

"If you're making minimum wage in a ski resort town, the gap between your benefits and the actual cost of feeding your family is massive," Blonsky adds. "That's a fundamentally different problem than what we see in less tourist-driven areas of the same state."

For health departments and community organizations, understanding gaps like this one can help target interventions more effectively — whether that's advocating for benefit adjustments, supporting local food banks, or creating community meal programs.

Where Can Folks Actually Use SNAP Benefits?

Even if benefits were adequate, another question looms: where can people spend them?

Metopio tracks the proportion of convenience stores that accept SNAP benefits as a proxy for food access. In some rural counties, convenience stores are the only SNAP retailers available.

"Take McMullen County in Texas," Elliott points out. "If you're on SNAP benefits there, your only options are convenience stores or leaving the county entirely. And if you don't have a car, that second option isn't really an option at all."

Blonsky underscores the compounding nature of these barriers: "When you filter for counties where a high proportion of people don't have cars and where SNAP retailers are mostly convenience stores, you start to see communities where food insecurity isn't just about money. It's about geography, infrastructure, and access."

In these areas, addressing food insecurity requires more than nutrition education. It demands systemic solutions — mobile markets, transportation programs, or incentives for grocery stores to locate in underserved areas.

And the lack of full-service grocery stores compounds the problem. Metopio's grocery store density indicator reveals just how far some communities are from fresh, affordable food.

These aren't just inconveniences — they're health determinants. Research consistently shows that limited access to healthy food contributes to higher rates of diet-related chronic diseases, including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

The Obesity Connection: It's Not Just Behavior

Speaking of obesity, one of the most powerful insights from this data analysis is how food access and obesity rates cluster together.

"When we filtered for counties with high convenience store reliance, low vehicle ownership, and limited grocery store access, obesity rates were consistently elevated," Blonsky notes. "And that tells us something really important: obesity isn't just a behavior issue. It's a structural one."

For decades, public health campaigns have focused on educating people about healthy eating. But as Blonsky points out, "Everyone knows what healthy foods are. We've been teaching that in elementary schools for decades. The problem isn't always knowledge — it's access."

If the nearest grocery store is two counties away, you don't have a car, and your SNAP benefits can only be spent at a convenience store with limited fresh food options, maintaining a healthy diet becomes a logistical challenge, not just a personal choice.

"This is why data context matters so much," Elliott adds. "If your community has a high obesity rate, understanding the underlying access barriers helps you design interventions that actually address the root cause."

Who's Eligible but Not Enrolled?

Another often-overlooked indicator is the percentage of households in poverty that aren't receiving SNAP benefits.

"This one has such a long name that people sometimes skip over it," Elliott says. "But it tells us a lot about who's falling through the cracks."

State-to-state variation is immediately visible on this map, reflecting differences in how SNAP programs are administered. Some states have stricter work requirements. Others have asset limits that disqualify people with even modest savings or a second vehicle.

"Immigrants, whether documented or not, face additional restrictions," Blonsky explains. "And in wealthier communities, you sometimes see higher rates of eligible non-enrollment — whether that's due to stigma or access to other forms of support like generational wealth."

Layering Data for Smarter Interventions

The real power of Metopio's approach isn't just in having access to individual indicators — it's in being able to layer them together to see the full picture.

By combining SNAP meal gaps, vehicle ownership, grocery store density, convenience store reliance, and obesity rates, community health teams can identify the areas facing the most compounded barriers. Those are the places where interventions need to be comprehensive, not piecemeal.

"It's not just about who is currently food insecure," Blonsky says. "It's about who's at risk. What factors are putting them at risk? Is it transportation? Is it the lack of a grocery store? Is it all of these things together?"

Understanding those upstream factors allows organizations to design programs that get to the root of the problem — whether that's advocating for policy changes, partnering with transit agencies, or working with retailers to expand SNAP acceptance and grocery access.

From Insight to Action

Food insecurity is one of the most complex social drivers of health, and the data reflects that complexity. But with the right tools, public health departments and hospitals can move beyond surface-level metrics and develop interventions that truly meet their communities' needs.

"We're not just tracking who's hungry," Elliott says. "We're tracking why they're hungry — and that's what makes the difference between a program that sounds good and one that actually works."

Metopio's platform makes it easy to explore these interconnected indicators, filter for at-risk populations, and design data-driven strategies that address food insecurity at its source.

““When you’re designing a program, you have to consider all of these factors together to make sure what you’re building really gets to the root of what’s going on.” ”